The Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) poses a growing threat to a number of US policy interests. Although most ASALA attacks have been against Turks, West European and a few US facilities have also been struck. Moreover, an apparent increase in contacts with Libya and Syria may expose the Marxist-oriented ASALA to additional anti-American influences. The rightwing Armenian terrorist group, the Justice Commandos for the Armenian Genocide, has focused almost exclusively on Turkish targets.

In a development that has ominous implications for international cooperation against terrorism, several West European nations have apparently reached accommodations with ASALA, allowing the terrorists freedom to pursue Turkish targets in exchange for promises not to attack indigenous citizens. The Turks have responded angrily against what they see as European indifference to or connivance with ASALA terrorism. They are strongly pressing the United States both to put pressure on European governments and to give more direct assistance in combating that threat.

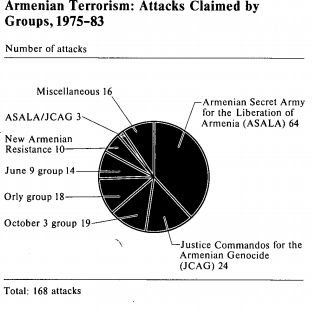

Despite some setbacks, the major Armenian terrorist groups retain considerable capability. ASALA and the Justice Commandos have assassinated 50 Turkish officials and private citizens and have conducted over 200 bombings since 1975. ASALA’s shift toward indiscriminate violence during the past four years makes large-scale casualties more likely as the group targets commercial aircraft and crowded public places. Recent fragmentation within ASALA and Armenian political groups, in our estimation, increases the risk of terrorist violence, particularly in Western Europe, as the various splinter groups vie for the attention of the Armenian community.

Background to Armenian Terrorism

Armenian terrorist groups ostensibly want to create an independent Armenian homeland. Most of the historic Armenian homeland was conquered in the mid-13th century by the Ottoman Turks, who moderated Armenian discontent by the distinctive Ottoman “millet” system. This gave Armenians and other minorities a large measure of independence in exchange for passive political loyalty. Armenians lived in their own communities and practised their faith and customs under the leadership of the Armenian patriarch. Over time, the ethnic cohesiveness encouraged by the millet system fostered nationalism within the Ottoman Empire. Serbs, Greeks, and Bulgarians, with the assistance of interested Western powers, forged their own identities and agitated for autonomous nation-states.

Armenian revolutionary groups at the end of the 19th century sought to establish an independent Armenian state. During World War I, some Armenians in eastern Turkey allied themselves with the Russians in the belief that Russian assistance later would guarantee an independent Armenia. Reported Armenian “fifth column” activities against the hard-pressed Ottoman state led to the deportation of Armenians from eastern Turkey into what is Syria today. Turkish bureaucrats, under imprecise orders, treated local Armenian populations as traitors. During the forced summer march of 1915, tens of thousands of Armenians died en route or were slaughtered by local groups, including Kurdish tribesmen. Estimates of the total death toll range from 600,000 to 1.5 million, providing an emotional rallying point used by Armenian terrorist groups to justify their actions. Today 50,000 of the 60,000 Armenians in Turkey live in Istanbul, which has become the seat of the Armenian Gregorian Church in Turkey and Patriarchate.

ASALA was formed in January 1975. Its declared goals include “liberation” of traditional Armenian lands—encompassing parts of present-day Turkey, Iran, and the Soviet Union—payment of reparations by the Turkish Government, and public acknowledgement by the Turkish Government of the 1915 genocide. Moreover, in accord with its Marxist-Leninist ideology, ASALA advocates armed struggle to achieve the liberation of Armenia and to further the interests of the exploited classes. ASALA has stated that its revolutionary theory distinguishes it from the other major Armenian terrorist group, the rightwing Justice Commandos for the Armenian Genocide (JCAG).

ASALA appears to be a group of young revolutionaries, most in their twenties and living or having lived in Lebanon. An ASALA terrorist captured in 1982 said that ASALA was organized along military lines into what he called brigades or divisions. Until recently we knew little about the ASALA decisionmaking process or the identities of the leadership core.

Apparently a central committee—whose location is unknown— oversees the group’s activities, ASALA originally used sup-port apparats—overt, legal groups—which, in our view, probably provided surveillance, propaganda, and logistic assistance for ASALA terrorist operations. These support groups—Popular Movements for the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (PMASALA)—were active in Paris, London, and Ottawa.

Justice Commandos for the Armenian Genocide

The second prominent Armenian terrorist organization, the Justice Commandos for the Armenian Genocide (JCAG), is a rightwing, nationalistic group without links to AS ALA, other terrorist groups, or patron states. JCAG, like AS ALA, demands an Armenian homeland and official Turkish recognition of the 1915 Armenian genocide.

We believe the Justice Commandos were created in 1975 by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF)—also known as the Dashnag Party—the most important and powerful Armenian political organization. The ARF was founded in 1890 by a group of Armenian intellectuals in the Transcaucasus region of Russia, as a response to violence committed against Armenian people under the rule of Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid. From its inception, the ARF has aligned itself with whoever provided the best opportunity for an autonomous Armenian state.

Since the end of World War II, the ARF has held a conservative, anti-Communist ideology and has been involved in violence against both the Turks and the Soviets, whom they hold responsible for the destruction of the Armenian republic in 1920.

Our analysis and a large body of evidence indicate that JCAG is the active wing of the ARF. We suspect that the ARF created a military wing to counter the emergence of the Marxist-Leninist ASALA, which was probably drawing the more radical, violence-prone youth away from the ARF. Competition between JCAG and ASALA has been keen during the past few years. Several terrorist attacks against Turkish interests have been claimed by both groups, and the success of one group sometimes seems to spur the other to act. We have also seen a few instances of members defecting from one group to the other, presumably not out of ideological conversion but simply to have greater opportunities to conduct operations against Turks. The prominent English-language publication Armenian Reporter cites the August 1983 conviction in Los Angeles of an ASALA member—the son of a prominent ARF leader—as evidence of the growing disenchantment and desertion of Dashnag youth to more active radical groups such as ASALA.

JCAG has operated predominantly against Turkish targets. Its attacks—usual assassinations of high-ranking Turkish diplomatic personnel conducted in public places during daylight hours—exhibit boldness, professionalism, and meticulous planning and training. JCAG employs surveillance/countersurveillance techniques to ensure the success of its operations. Its infrequent bombings of Turkish facilities, which appear to be conducted as warnings to Turkish diplomats, are followed within two or three months by assassination attempts.

In contrast to ASALA, JCAG has not yet conducted or threatened to conduct reprisal attacks to force the release of captured operatives, who are considered “un-uniformed soldiers" by JCAG. We believe JCAG assassins—only rarely apprehended—are recruited and trained within the ARF Youth Federation on a one-time "kill” basis. After an assassination, the JCAG operative is seldom used again in a terrorist operation.

ASALA’s headquarters in West Beirut was severely disrupted by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in June 1982 and the subsequent expulsion of the Palestinians.

We believe ASALA did fragment, with some members in France and Syria; however, we suspect a portion of the ASALA membership has remained in Beirut, perhaps in an inactive status.

Changing Tactics and Organization

ASALA’s tactics—assassinations and bombings— have undergone major changes during the past four years; the most important shift has been ASALA’s willingness to attack targets involving non-Turkish victims. In 1979 ASALA began targeting Western interests—especially French and Swiss—in retaliation for arrests of ASALA members. ASALA has also conducted hostage operations—sieges at the Turkish Embassy in Tehran and Paris during 1981—aimed at attracting sustained public attention. A more lethal shift in tactics surfaced in the Orly Airport bombing on 15 July 1983, which killed eight and wounded 55. The bomb, planted in a suitcase, had been intended to explode while the Turkish airliner was in flight, which would have caused scores of casualties.

A mid-1982 upsurge in indiscriminate violence by ASALA—using the cover name Orly Group—provoked changes within the organization.

In our view, ASALA jettisoned its support groups because of their reluctance to support ASALA’s violent campaign against non-Turkish targets. The discarding of ASALA’s support apparat resulted in further changes in ASALA’s infrastructure.

We also believe that there is a parallel Europe-wide effort by ASALA to develop a broad base of support for its political goals.

A press release of 28 July announced that the congress had created an Armenian Liberation Organization dedicated to international political efforts to gain an Armenian homeland. Failure by the congress and the new political organization to condemn Armenian terrorist violence may indicate that pro-ASALA delegates control both groups.

ASALA’s indiscriminate violence has also provoked fragmentation within the terrorist ranks. A new splinter group—the ASALA Revolutionary Movement— was formed in Beirut in August 1983, pledging to continue the armed struggle but only against what they consider legitimate “military targets.” We interpret “military targets” to mean Turkish diplomatic and official installations.

ASALA has made contradictory statements regarding its relations with West European terrorist groups. Claims by some ASALA members of operational ties to the Italian Red Brigades and the Spanish Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) terrorists have been denied by ASALA spokesmen and communique. ASALA has also claimed an alliance with the Kurdish Worker’s Party (KWP) and joint participation, with the KWP, in an attack on the Turkish Consulate 25X1 in Strasbourg, France, in November 1980. No other claims of joint operations have been issued.

Foreign Government Links

Although Syria has given little assistance to ASALA in the past, we believe that this is changing in the wake of the invasion of Lebanon and the resulting evacuation of some ASALA members to Damascus.

Iran

Although ASALA initially supported Khomeini’s revolution, the 1981 execution of two ASALA members in Iran and the recent repression of Armenians there have caused ASALA to reverse its position. According to an Armenian nationalist journal, Khomeini is engaging in religious persecution of Armenians, including the closure of Armenian schools and the imposition of a “non-Islamic” tax on the Armenians. The Armenian Center in Isfahan was attacked by Revolutionary Guards in April 1981—on the anniversary of the genocide observed by Armenians around the world. Since the arrests of 51 Armenians in Paris after the Orly bombing, French installations in Tehran have been the target of several attacks by the Orly Group (an ASALA covername). We suspect these attacks may have been conducted with Iranian approval if not assistance. Franco-Irani-an relations have been severely strained in the wake of French Government sanctuary for dissident Iranian hijackers of an Iranian aircraft in July 1983 and the sale of French military equipment to Iraq.

The French Connection

France at one time also maintained an informal channel with ASALA. This conduit may have facilitated negotiations after the arrest of the four ASALA members who, on 24 September 1981, seized the Turkish Embassy in Paris and killed a guard in the process. ASALA claimed that the police had promised political asylum for the ASALA members in return for their surrender and publicly gave the French until 22 November 1981 to release the four terrorists. In the absence of French action, ASALA resumed its attacks two days after the deadline. ASALA later announced that it was halting its attacks against French interests because the government had agreed to give the prisoners political status. This “truce” was broken after French authorities arrested Vicken Tcharkhutian in June 1982 for suspected involvement in a bombing in the United. States. That summer ASALA conducted two bombings in Paris but halted its attacks once more when the French court refused to extradite Tcharkhutian to the United States. Tcharkhutian was subsequently released from custody and permitted to go to the Middle East. In January 1983 ASALA resumed its activity against Turkish targets in France.

Accommodation With Italy

ASALA has tried to arrange an agreement with Italy to halt the emigration of Armenians from their traditional homelands in the Soviet Union. ASALA called for the closure of all emigration centers in Italy on 22 December 1979 when the group attacked a Rome pension that housed Armenian emigrants. Hagopian claimed in a February 1982 interview that an agreement had been reached under which ASALA would not conduct attacks in Italy except against Turkish targets. In return, the Italians would close the emigration offices within six months. Although Hagopian later said that the Italians reneged by simply moving the offices and changing their names, there have been no more ASALA attacks in Italy.

The Turkish Response

Armenian terrorism is a serious domestic political issue. Unlike other political issues in Turkey, however, it arouses no significant disagreement along right-left lines. Most Turks, regardless of their political views, share a common reaction to Armenian terrorism— anger, revulsion, and an intransigent unwillingness to accept the Armenian version of history. There is little disagreement across the Turkish political spectrum that Armenian terrorism should be dealt with firmly and directly.

The ASALA attack at Ankara’s airport in August 1982—the first significant Armenian terrorist attack inside Turkey since 1979—focused public concern in Turkey on the threat posed by Armenian terrorists. Ankara’s twofold public approach to the problem— refuting Armenian charges of genocide and threatening retaliation by Turkish “hit squads”—failed to still Armenian propaganda or halt terrorist attacks. Through diplomatic channels, the Turkish Government attempted to pursue coordinated international efforts to thwart Armenian terrorism.

Enhanced security precautions at Turkish installations also failed to deter terrorists whose fanaticism had, in some cases, reached “suicide operation” proportions or whose skill and planning was superior to Turkish defensive measures.

the Turkish Government has begun exploring more active counterterrorist methods. We believe the training of commandos to strike against Armenian terrorists was initially aimed at defusing criticism within the Turkish Government of Evren’s soft approach to terrorism. Although Turkish leaders have approved plans for using these squads, such a move would be politically costly. Turkey’s military rulers are already smarting from the intense West European criticism of martial law and human rights abuses. We do not believe the government of Prime Minister Ozal would jeopardize military and economic aid from West European countries by officially and publicly sanctioning such attacks, which will be played up by the Armenian press.

The Armenian community in Turkey is unsympathetic to the terrorist groups. The Patriarch of the Armenian Gregorian Church in Istanbul has consistently spoken out, condemning the violence. Opposition to the terrorists derives principally from the community’s fear that further attacks against Turkish interests might induce the Turks—frustrated by their government’s inability to deal with the extremists abroad— to retaliate against Armenians in Turkey.

Impact on US Interests

The direct threat to American interests only emerged with the mid-1982 imprisonment of Armenian terrorists in the United States. On 30 May 1982, three ASALA terrorists were arrested for attempting to bomb the Air Canada freight terminal in Los Angeles. The bomb was intended to gain freedom for four Armenians who had been arrested in Toronto and were charged with conspiracy to extort money from wealthy Armenians in Canada. The conviction of the three ASALA members has not resulted in any retaliatory attacks to date, although, given ASALA’s past record, attacks might still be conducted in an attempt to force the judge into giving the prisoners light sentences.

The activities of Armenian terrorist groups have caused some tension between Ankara and Washington. Implying that Western intelligence agencies are withholding information, the Turks have pressed for specific identities, locations, and plans of Armenian terrorists. The United States does share information with the Turks, but US legal constraints prohibit the passage of information concerning US citizens and subjudice material. Several West European countries are legally limited from providing information on suspected Armenian terrorists who also hold citizenships in those countries.

The Turks have requested US training in defensive counterterrorism techniques. A US-Turkish Committee on Armenian Terrorism was formed in 1982 in Ankara to discuss joint cooperation efforts, and the anticipated passage of legislation to fund the protection of foreign consular personnel in the United States may also ease Turkish pressure.

Outlook

We believe the fragmentation within ASALA increases the threat of terrorist violence. The splintering of ASALA1—as well as the continuing threat from the Justice Commandos—presage a struggle among the groups for support from the Armenian populace. We expect attacks against Turkish targets to be the focal point for this struggle. We believe that the failure of the Armenian Congress to renounce terrorist violence may be perceived by the terrorists as a green light to conduct attacks as a means of swaying Armenian public opinion to their cause. US residents, citizens, and property may also be future targets of Armenian terrorist groups, especially if the trend toward indiscriminate violence continues.

Neither stepped-up enforcement nor intelligence activities have noticeably impaired Armenian terrorist capabilities. Recent attacks show that Armenian terrorists can strike with virtual impunity. We suspect that ASALA’s expanded contacts with Libya may eventually increase the group’s terrorist potential. We believe Syrian involvement with ASALA may also bolster Armenian capabilities, particularly if Syria is providing training and' a base of operations for ASALA terrorists.

We expect that future Armenian attacks will increase the pressure on the Turkish Government to take strong action. Armed Turkish retaliation could further damage Ankara’s international image and strain relations with other European nations. Any Turkish retaliation against Armenian terrorists would result in sharp Armenian retribution, probably in the form of more frequent and lethal attacks. Ankara will encounter added frustration as it pressures Washington and other NATO members for a unified international approach to terrorism.

Read the original article on the library documents of the CIA .